Examining Medical Care of Unhoused Individuals in the Skid Row Community

Ahmad Elhaija (1,3,*), Charlie Black (2,3), Shubhreet Bhullar (2,3)

-

David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA, aelhaija@ucla.edu

-

Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, 1285 Franz Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

-

International Healthcare Organization, Los Angeles, CA, USA

*Corresponding authors.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58417/QLAD3062

Structured Abstract

Background: The homeless population in Los Angeles, particularly in Skid Row, faces increasing healthcare challenges despite available resources. Limited access to consistent and comprehensive care contributes to a high burden of chronic diseases and mental health conditions in this community.

Aims: This study evaluates the healthcare needs of Skid Row residents to identify gaps in care and inform targeted interventions that improve health outcomes.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey of 163 adult Skid Row residents was conducted to assess healthcare access, medical conditions, and unmet needs. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to identify prevalent health concerns and barriers to care.

Results: Among respondents, 84.4% were currently experiencing homelessness, and 78.0% had health insurance, yet substantial gaps in care remained. Mental health concerns were reported by 42.8% of participants, 89.7% of whom had comorbid conditions. While 62.3% were covered by Medi-Cal, 32.4% lacked a stable medical provider.

Conclusions: The findings underscore the urgent need for integrated healthcare solutions that address both medical and social determinants of health. Interventions like the International Healthcare Organization's HealthNet Program and Prescription Medication Assistance Program can enhance access to continuous, patient-centered care, ultimately improving health equity for Skid Row's homeless population and other underserved communities. These programs also serve as effective models for developing similar interventions to address healthcare disparities more broadly.

Introduction

With a 10% increase in the homeless population from 2022 to 2023, the housing crisis faced by Los Angeles (LA) is at an all-time high (1). LA County receives over one billion dollars for combatting the housing and homelessness issues it faces (2). Despite the funding and numerous programs and initiatives in place, the number of people experiencing homelessness (PEH) increases, and the problems faced by the homeless remain. Particularly, PEH often experience extensive gaps in access to healthcare, leading to high usage of more intensive medical care services such as hospitalizations (3). Compounding this issue, PEH are additionally vulnerable to various syndemic health threats due to a high-risk environment (4). The medical care of unhoused individuals in Los Angeles represents a complex and multifaceted challenge that intersects with issues of mental health, substance use, chronic illnesses, and social determinants of health. The issue of homelessness in LA is most acute in Skid Row, a four-square-mile region housing 4,500 of LA County’s homeless population.

Despite various initiatives and programs aimed at addressing PEH’s extensive healthcare needs, significant gaps persist in effectively meeting the needs of this vulnerable population. Unhoused individuals, particularly young adults, often experience unmet medical needs, most commonly in regard to mental health, even when transitioning to supportive housing. A study examining medical needs among young adults who have experienced homelessness in Los Angeles found that those in supportive housing reported more unmet healthcare needs than their unsheltered counterparts, potentially due to shifting priorities during the transition (5). The mental health challenges faced by unhoused individuals further complicate medical delivery. Research indicates that homelessness is associated with longer psychiatric hospital stays. Furthermore, preliminary research propounds a correlation between hospitalization, comorbidity, and mental illness within homeless communities (6). While mental health conservatorship can aid in transitioning individuals to treatment, previous research indicates that this form of intervention does not directly provide long-term housing solutions and expends a large amount of resources (7).

Mortality rates among PEH in Los Angeles County have been on the rise, with drug overdoses being the leading cause of death. This alarming trend underscores the urgent need for targeted interventions and comprehensive healthcare strategies (8). Additionally, the duration and frequency of homelessness episodes are critical factors influencing health outcomes, with long-term unsheltered young adults exhibiting significantly poorer health outcomes, including higher rates of mental health and substance use disorders (9). Moreover, end-of-life care for homeless individuals is often neglected, necessitating tailored approaches that address their unique needs and preferences (10).

Homelessness creates environments that amplify physical health issues, such as musculoskeletal problems, which are often both consequences of and contributors to broader social determinants of health (11). Suboptimal sleeping conditions and decreased physical activity exacerbate these issues, leading to a cycle of declining mobility and reduced quality of life (11). For example, the fact that the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions among PEH requires both continuous care and improvements in living conditions elucidates how intricately intertwined challenges like food insecurity, inadequate medical care, and mental health comorbidities are (12). This interplay between physical and mental health demonstrates how the cumulative effects of homelessness create compounding barriers to achieving equitable care.

The frequent use of emergency medical services, particularly for psychiatric reasons, by homeless individuals also reflects the broader healthcare disparities and unmet needs within this population (13). Specifically, homeless women face distinct health challenges related to drug abuse, violence, and depression, highlighting the need for medical services prioritizing this group (14).

The complexity of providing continuous care to unhoused individuals to support the litany of medical issues faced by PEH highlights a need to understand the healthcare issues faced by the homeless community in Skid Row so they may be systematically addressed (15). To better understand the medical needs of the PEH in Skid Row and develop a more targeted approach, the International Healthcare Organization (IHO) sought to conduct a community health assessment of individuals in Skid Row.

IHO is a 501 c(3) non-profit organization based in Los Angeles, California, composed of doctors, nurses, medical students, non-profit advisors, and healthcare administrators (16). IHO began as an organization dedicated to direct service in the community through its sanctuary health clinics in the Southeast Los Angeles area. Over time, IHO grew its impact by expanding its provided services to communities across the United States and the globe. Through its implementation of unique healthcare safety-net systems, IHO enhanced patient care by providing immigrant, refugee, and homeless populations with comprehensive educational, medical, and mental health services. IHO’s community health assessment report discusses the findings and a review of the literature on community-based solutions for addressing the unmet needs of this vulnerable group.

This study inquires into the implications of the intricate relationships between morbidity, mental health, and homelessness on the design of targeted interventions intended to improve health outcomes of the homeless population in Los Angeles.

Materials and Methods

This study used a cross-sectional survey approach to conduct a community needs assessment, utilizing numerically answered questions, yes or no questions, and open-ended response questions. The survey consisted of questions relevant to the demographic information and medical treatment of the target population. Participants were asked questions regarding age, gender, last physician checkup, housing, medical services received, medical conditions, and medical needs. Respondents individually completed the survey provided in paper format with the provided pens. The respondents were encouraged to ask the surveyors questions whenever they were uncertain regarding the questions, particularly in regards to understanding the operational definitions of the questions and certain specific nuances when answering certain questions.

For this research process, a problem was initially identified and then relevant data was collected. IHO team members conducted a convenience sample of Skid Row adults recruited from the Midnight Mission rehabilitation center, the Union Rescue Mission common area, and the streets of Skid Row. 163 adult individuals responded to our survey, all of whom provided informed consent. Following data collection, the data was evaluated and analyzed before its findings could be presented. A descriptive analysis of data was conducted from our medical care survey, with percentages and mean answers to the survey questions being calculated. The data was inspected to gain insights regarding the unique integration of medical services for this community.

This study was designated as exempt from IRB approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), since no identifying information was taken, the participants remained anonymous, no invasive interventions were done, the study was completely optional, and all participants expressed informed consent prior to participation.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients and members of the Skid Row community were actively involved in this study through their participation in the survey. A total of 163 adult participants provided first hand insights into their healthcare experiences, access to medical services, and barriers to chronic disease management. While participants were not directly involved in the study design or data analysis, their responses fulfilled a critical role in shaping the study’s findings and implications. Future research may benefit from incorporating community stakeholders in the development of survey instruments and interpretation of results to further align research objectives with the needs of this population.

Results

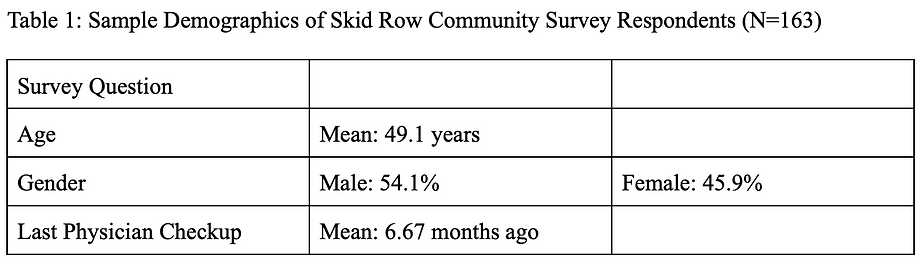

Our survey findings elucidate that despite 78.0% of the Skid Row population having health insurance, there is still a high prevalence of health conditions and a desire for increased access to medical care. 84.4% of the Skid Row community self-identified as homeless and 76.9% were looking for housing. 62.3% of the individuals with health insurance have MediCal. 32.4% of the people surveyed were seeking a stable medical provider, 75.7% were interested in screening services, and 41.6% believed that they lacked nutritional assistance, indicating a large percentage of individuals desired additional medical care resources that are not currently available to them. Of the Skid Row residents that were surveyed, 17.2% were undergoing substance treatment and 21.4% had injuries at that time. While only 8.1% had chronic heart disease and 2.3% had cancer, 42.8% were struggling with mental health, 18.5% had respiratory disease, and 40.5% had hypertension. 32.8% of the population had more than one medical affliction. The majority of responses to utilizing potential financial assistance for housing help shine a light on the most significant need of Skid Row’s community. The key highlights from the aforementioned data alongside demographic information can be seen in Table 2 and Table 1 respectively.

Mental health emerged as a critical issue in our dataset, with 47.6% of respondents reporting mental illness. Within this subgroup, 89.7% also experienced at least one co-occurring health condition, compared to 44% among those without reported mental health struggles (MHS). Notably, individuals with mental illness were more likely to have used (63.2% vs. 46.7%) and currently use non-prescription medications (26.5% vs. 14.7%). Furthermore, individuals with mental illness reported shorter intervals since their last physician visit (4.06 months vs. 6.88 months). Despite higher percentages of individuals with MHS using non-prescription medications, only 19.1% of them underwent substance abuse treatment. This highlights a pattern of acute healthcare utilization, reflective of unmanaged or exacerbated mental health conditions. The key highlights from the data can be seen in Table 3.

Discussion

The findings from our Skid Row survey highlight the significant healthcare challenges faced by the homeless population in Los Angeles. Despite 78.0% of respondents having health insurance, 62.3% were specifically covered by MediCal, indicating potential gaps in coverage adequacy. The data revealed that 84.4% identified as homeless and 76.9% were seeking housing. A notable 32.4% of respondents were looking for a stable medical provider, 75.7% expressed interest in screening services, and 41.6% felt they lacked nutritional assistance.

These findings emphasize the multifaceted nature of the health needs of the homeless population, particularly in mental health and chronic disease management. This high prevalence highlights the impact of systemic barriers like limited access to mental health resources and societal stigma. Mental health emerged as a critical concern, with 47.6% of homeless respondents reporting mental illness. This is consistent with previous research revealing high rates of psychiatric disorders among homeless populations in high-income countries (17). This displays the observed interaction of mental illness with other health conditions, as 89.7% of those reporting mental health struggles also had at least one co-occurring condition. This high rate of comorbidity suggests that for PEH in Skid Row, mental health issues are closely related to their physical health conditions. For instance, untreated depression can lead to poor diabetes management due to missed appointments and lack of self-care. The reverse relationship between mental health and physical health may also be actively contributing to this complex issue.

Alongside a higher rate of comorbid conditions, these individuals were observed to have a higher likelihood of using and relying upon non-prescription medications. Additionally, our data suggests PEH in Skid Row have an average higher frequency of healthcare utilization compared to their counterparts without mental illness. The average time since a physician visit for individuals without mental illness was 6.88 months, contrasting sharply with 4.06 months for those with mental health struggles, suggesting a discrepancy in care-seeking behavior driven by acute need. While the exact reason for this relationship remains unknown, a possible reason may be a significant reliance on over-the-counter remedies as a substitute for consistent medical care. This could be driven by barriers such as limited access to healthcare providers, stigma, and often fragmented mental health services. The stigma around mental health, coupled with long wait times at community clinics, often leads individuals to rely on emergency services. Frequent healthcare utilization reflects the cyclical nature of unmanaged physical and mental health conditions (11), often leading to health crises requiring immediate intervention.

These findings highlight the syndemic nature of health challenges in this population, where social determinants like unstable housing, food insecurity, and substance abuse exacerbate health disparities. Physical health conditions also remain prevalent among Skid Row’s homeless population, with 18.5% reporting respiratory diseases, 40.5% reporting hypertension, and 21.4% reporting general injuries at the time of the survey. Chronic conditions, compounded by inadequate access to consistent care, illustrate the urgency for integrated healthcare solutions tailored to this vulnerable group.

These medical care challenges are exacerbated by the instability and transience inherent in the lives of Skid Row’s homeless population. Even with insurance, the instability of homeless individuals’ lives often disrupts continuous care, leading to gaps in continuous treatment plans (18). Health challenges also vary widely within the homeless population, with subgroups like unsheltered young adults requiring tailored care for their unique challenges (19). These variations within the population further complicate creating a comprehensive solution to healthcare needs in this population. Social determinants such as food insecurity, lack of stable housing, and mental health issues only further compound these challenges (20). High-risk living conditions, including substance abuse and violence, exacerbate health problems. The prevalence of syndemic conditions among homeless individuals—where the interaction of diseases and social factors mutually exacerbate one another—illustrates the profound impact of upstream social determinants on health outcomes (9). For example, a lack of stable housing can lead to poor nutrition, which worsens chronic diseases like diabetes.

The high rates of physical and mental conditions clearly depict the urgent need for integrated medical services prioritizing preventative measures to improve long-term health outcomes. Furthermore, co-designing these interventions with PEH from the community has resulted in centralized healthcare programs that have shown greater efficacy in reducing mental and physical conditions in the population (21). Centralizing medical, mental health, educational, and basic necessity resources would allow PEH to address their often comorbid conditions while also providing tools to prevent the development of further issues. This approach would mitigate barriers such as transportation and care continuity, enabling effective management of comorbid conditions. Additionally, the provision of on-site mental health services is vital, as previous studies have shown that integrating behavioral health into broader medical programs significantly reduces psychiatric hospitalizations and fosters stability in housing transitions (6).

Previous interventions created in similar communities have utilized many methodologies to provide effective treatment. Community-institutional partnerships have previously been effective in providing a range of services from preventative to specialty care (22). However, there is a lack of programs developed to specifically address social determinants of health alongside mental and physical health (22).

The community health assessment’s findings emphasize the critical need for healthcare interventions in Skid Row (20). In response to these findings, the International Healthcare Organization (IHO) is actively working to address these healthcare disparities through innovative interventions. One of IHO’s key strategies is the implementation of a comprehensive Health Net Program to provide free or reduced cost primary and specialty care services to residents of Los Angeles, focusing particularly on underserved populations. The Health Net Program includes services in pulmonology, dermatology, behavioral health, and more, ensuring a broad spectrum of medical needs are met. Additionally through IHO’s Complete Cognitive Care program, telehealth services are being provided to further increase access to psychiatric and behavioral care services.

The introduction of these specialized clinics within programs like the Health Net Program is a crucial step in providing holistic care to the homeless. These clinics are designed to offer not only specialty services but also to coordinate with other medical providers to address the complex needs of underserved populations. This approach aligns with existing literature emphasizing the importance of targeted interventions and comprehensive care strategies to improve health outcomes among people experiencing homelessness.

Furthermore, the integration of behavioral health services into broader healthcare programs addresses the specific challenges faced by homeless individuals with psychiatric conditions. PEH experience higher than average rates of mental illness and psychiatric disorders, contributing to medical care issues (18). Research has indicated that homelessness is associated with longer psychiatric hospital stays, and while mental health conservatorship can aid in transitioning individuals to treatment, it does not guarantee long-term housing solutions. IHO’s Health Net Program aims to bridge this gap by providing continuous mental health support, thus reducing the likelihood of repeated hospitalizations and enhancing the stability of housing transitions (6).

Another critical intervention aimed at reducing healthcare disparities among PEH employed by IHO is the Prescription Medication Assistance Program (PMAP), which ensures that PEH have access to necessary medications at low or no cost. This initiative is particularly important given the high prevalence of chronic conditions such as hypertension and respiratory diseases among our respondents. By providing affordable medications, PMAP helps to manage these conditions effectively, reducing complications and improving overall health outcomes.

These initiatives align with IHO’s goal of improving health equity and health outcomes in underserved communities and reflects IHO’s commitment to addressing the social determinants of health and providing sustainable healthcare solutions for the most vulnerable members of our society (23). By focusing on the unique needs of the homeless population in Skid Row, IHO aims to develop a model of care that can be replicated in other regions facing similar challenges.

While there are several different ways to formulate an intervention addressing the factors detailed above, IHO’s efforts can serve as a preliminary example of integrating a wide range of medical services into broader healthcare strategies. Ultimately, further interventions formed for this population should prioritize mental health alongside physical health while also ensuring the multifaceted medical care needs of unhoused individuals are met effectively and sustainably.

Works Cited

-

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2023, June 29). Lahsa releases results of 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless count. Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=927-lahsa-releases-results-of-2023-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count

-

Los Angeles County Department Of Mental Health. (2021a, June 22). MHSA THREE-YEAR PROGRAM AND EXPENDITURE PLAN Fiscal Years 2021-22 through 2023-24 . Los Angeles.

-

Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2011). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326–1333. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.180109 Baggett 2010 - 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109

-

Robinson, A. C., Knowlton, A. R., Gielen, A. C., & Gallo, J. J. (2015). Substance use, mental illness, and familial conflict non-negotiation among HIV-positive African-Americans: Latent class regression and a new syndemic framework. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9670-1

-

Semborski, S., Henwood, B., Madden, D., & Rhoades, H. (2022). Health care needs of young adults who have experienced homelessness. Medical Care, 60(8), 588–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001741

-

Klop, H.T., de Veer, A.J., van Dongen, S.I. et al. Palliative care for homeless people: a systematic review of the concerns, care needs and preferences, and the barriers and facilitators for providing palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 17, 67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0320-6

-

Choi, K. R., Castillo, E. G., Seamans, M. J., Grotts, J. H., Rab, S., Kalofonos, I., Mead, M., Walker, I. J., & Starks, S. L. (2022). Mental health conservatorship among homeless people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 73(6), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100254

-

Nicholas, W., Greenwell, L., Henwood, B. F., & Simon, P. (2021). Using point-in-time homeless counts to monitor mortality trends among people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County, California, 2015‒2019. American Journal of Public Health, 111(12), 2212–2222. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306502

-

Richards, J., Henwood, B. F., Porter, N., & Kuhn, R. (2023). Examining the role of duration and frequency of homelessness on health outcomes among unsheltered young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 73(6), 1038–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.06.013

-

Klop, H. T., de Veer, A. J. E., van Dongen, S. I., Francke, A. L., Rietjens, J. A. C., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2018). Palliative care for homeless people: A systematic review of the concerns, care needs and preferences, and the barriers and facilitators for providing palliative care. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0320-6

-

Marmolejo, M. A., Medhanie, M., & Tarleton, H. P. (2018). Musculoskeletal Flexibility and Quality of Life: A Feasibility Study of Homeless Young Adults in Los Angeles County. International journal of exercise science, 11(4), 968–979.

-

Seto, R., Mathias, K., Ward, N. Z., & Panush, R. S. (2020). Challenges of caring for homeless patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders in Los Angeles. Clinical Rheumatology, 40(1), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05505-6

-

Kushel, M. B., Perry, S., Bangsberg, D., Clark, R., & Moss, A. R. (2011). Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: Results from a community-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 778–784. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.92.5.778

-

Teruya, C., Longshore, D., Andersen, R. M., Arangua, L., Nyamathi, A., Leake, B., & Gelberg, L. (2010). Health and health care disparities among homeless women. Women & Health, 50(8), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2010.532754

-

Feldman, B. J., Kim, J. S., Mosqueda, L., Vongsachang, H., Banerjee, J., Coffey, C. E., Spellberg, B., Hochman, M., & Robinson, J. (2021a). From the hospital to the streets: Bringing care to the unsheltered homeless in Los Angeles. Healthcare, 9(3), 100557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2021.100557

-

“International Healthcare Organization.” IHO, 6 Feb. 2024, www.ihealthcareorganization.org/.

-

Gutwinski, S., Schreiter, S., Deutscher, K., & Fazel, S. (2021). The prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLOS Medicine, 18(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750

-

Garcia, C., Doran, K., & Kushel, M. (2024). Homelessness and health: Factors, evidence, innovations that work, and policy recommendations. Health Affairs, 43(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01049

-

Richards, J., Henwood, B. F., Porter, N., & Kuhn, R. (2023a). Examining the role of duration and frequency of homelessness on health outcomes among unsheltered young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 73(6), 1038–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.06.013

-

Elhaija, A., Chu, N., & Siddiq, H. (2023). Identifying the service needs of homeless individuals in the skid-row community. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 33(1), 258–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2023.2187273

-

Schiffler, T., Kapan, A., Gansterer, A., Pass, T., Lehner, L., McDermott, D. T., & Grabovac, I. (2023). Characteristics and Effectiveness of Co-Designed Mental Health Interventions in Primary Care for People Experiencing Homelessness: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010892

-

Lee, J. J., Jagasia, E., & Wilson, P. R. (2023). Addressing health disparities of individuals experiencing homelessness in the U.S. with Community Institutional Partnerships: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79(5), 1678–1690. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15591

-

Elhaija, A., Kodavatikanti, A., Dhaulakhandi, H., Alam, U. “Understanding the Relationship between Educational Attainment and Preventative Healthcare Utilization in Southeast Los Angeles.” Journal of Healthcare Solutions, 2025.